Panels and the Olympic Museum

by Mark Robins | 1 June 2020 12:00 am

Technology-driven modeling aids museum panels

The museum’s facade geometry incorporates double-curved surfaces, dissected by multiple isoperimetric curves. Wrapping this complex surface is a series of exterior façade systems consisting of glass curtainwall, sloping, curved aluminum composite material (ACM) panels, and over 8,500 unique diamond shape, 3-D rainscreen metal panels.

Complex Façade

The United States Olympic Museum’s complex façade geometry, defined by multiple curves and tangent lines, presented significant challenges in terms of modeling, fabrication, coordination and field execution. The variety of software platforms and tools used on this project, allowed for more efficient coordination with multiple trades, precise model-based fabrication, and sharing of critical data for installation in the field.

In establishing project controls, the architect’s direct surface model geometry was used as the basis of design. This model, in addition to the typical project controls (construction documents, specifications, sketches, etc.), were all integrated in a 3-D project master model. The master model was developed and refined in an initial design-assist process, and then extended into the entire life cycle of the project, encompassing coordination with other trades, fabrication, installation and quality control over the course of two-plus year process.

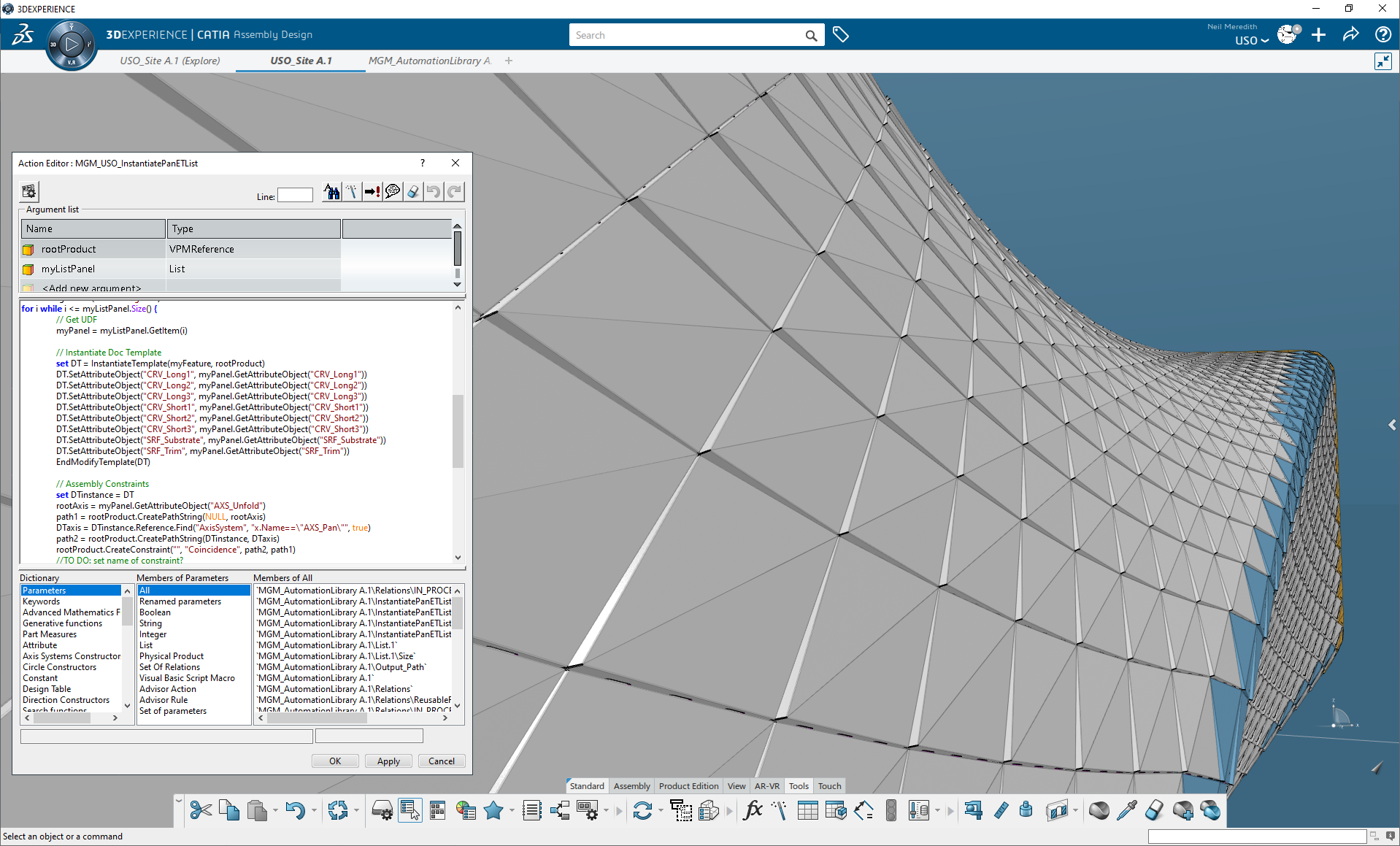

As a fabricator and installer of architectural surfaces, the project team developed a 3-D model workflow that would allow for a high degree of control over the fabrication of the metal panels for the building exterior. To manage that process, it was decided early in the project that a solid 1:1 fabrication model for every panel on the project, would provide the best result. Given the varying geometry, this was the only way to visually verify the panels at a high level of detail, before heading into the fabrication.

Typically, in sheet metal fabrication for buildings, the overall dimensions of the panels are unfolded and detailed in a 2-D environment to prepare the geometry for fabrication. Given the geometric complexity and tight tolerances of this design, the team decided to take a more manufacturing-like modeling process of solid-modeling all the panels. Additionally, the process needed to be automated and produced at a scale that would let us manage the production of the entire building at a high level of detail.

While the quality and constructability were the main constraints, there were two other constraints: the ability to rapidly change or modify panel designs due to a variety of construction or field constraints, as well as the need to scale the process to meet an aggressive production schedule for this number of unique parts. While having individually modeled solid parts is typical within a manufacturing type setting by where you make multiples of the same designed part, here we were dealing a single panel topology (basically a triangulated, four-edged panel) with almost 10,000 unique variations, each requiring their own CNC fabrication drawing, assembly drawing and field installation information. In the end, all panels were treated as unique panels.

Once this model is coordinated and checked, it can then be used as the inputs for the fabrication parts. This provides a few benefits. First, you have a 3-D model earlier in the process. If you rely on the completed fabrication model for upfront digital coordination, it will often come too late in the construction process to resolve any field conflicts before the panels are fabricated. Secondly, you can make changes to the driver model, and then have that change flow down to the affected fabrication parts without having to individually fix or modify each part every time there is a change. The resulting approach is one that balances the flexibility of a low level of detail wireframe model, with the ability to mock-up and produce panel fabrications with relatively complexity and speed.

Coordination between trades is vital to a successful projection execution. The façade BIM coordination on USOM involved multiple trades including concrete, structural steel, light-gauge metal framing, glass and glazing, rainscreen cladding, roofing and lightning protection. Each trade was responsible for modeling their components, sometimes down to individual nuts and bolts. The execution of this project would be impossible within the given time frame, budget and tolerances without the use of these technologies.

Lee Pepin is the director of virtual design construction, and Ilja Aljoskin is a project manager at MG McGrath Inc., Maplewood, Minn. To learn more, visit www.mgmcgrath.com[1].

- www.mgmcgrath.com: http://www.mgmcgrath.com

Source URL: https://www.metalconstructionnews.com/articles/panels-and-the-olympic-museum/