Exterior sunshades are commonplace on many building types. Many manufacturers offer them as an optional component of curtainwall systems. Unfortunately, when it comes to reducing first costs on buildings, many owners regard sunshades as a frivolous decoration, so they are often among the first cuts made during the value-engineering process. Following from the logical assumption that shading buildings reduces energy loads, one company set out to measure the environmental impacts of producing sunshades as part of a broader effort to develop sustainable— and profitable—products and practices.

Sunshades offer significant opportunities for both energy and cost savings

Sunshades Save Money

Our company, Industrial Louvers Inc., Delano, Minn., found quantifiable evidence that sunshades save building owners money. That is, over the course of both the building’s and the sunshade’s life cycles, sunshades offer significant opportunities for energy—and therefore cost—savings. In all cases, we found that the positive impacts of exterior sunshades far exceeded the costs associated with production and installation. Further, reductions in energy, carbon and water make the building more sustainable.

We embarked on this study as part of larger effort to produce sustainable products and operations. We decided to pursue the International Living Future Institute’s (ILFI) sustainability initiative for manufactured products, called the Living Product Challenge (LPC). The LPC encourages manufacturers to make products that are regenerative with respect to the resources they use. If that can be achieved, manufacturers can make the world a better place, and save customers money, with every product they sell.

The LPC is particularly useful because traditional environmental frameworks do not account for products’ regenerative potentials. Footprinting is the traditional framework used to describe negative environmental impacts. Many people have heard the term carbon footprint refer to the total greenhouse gas emissions associated with an activity or product. There are also footprints associated with the water, energy and other resources that go into everyday products and activities. Every person, product, service and organization creates footprints, meaning that every person, product, service and organization has an environmental impact.

Thinking about sustainability in terms of reducing footprints, or mitigating potential environmental harms, is only so useful. This framework does not accommodate for the vision our company and the LPC have: certain activities and products can help save resources, even reverse environmental harm that has already been incurred. Therefore, the LPC incorporates positive impacts, or the extent to which natural resources can be restored throughout a product’s life cycle, into its framework. The total environmental impact—the positive minus the negative—is called a product’s handprint.

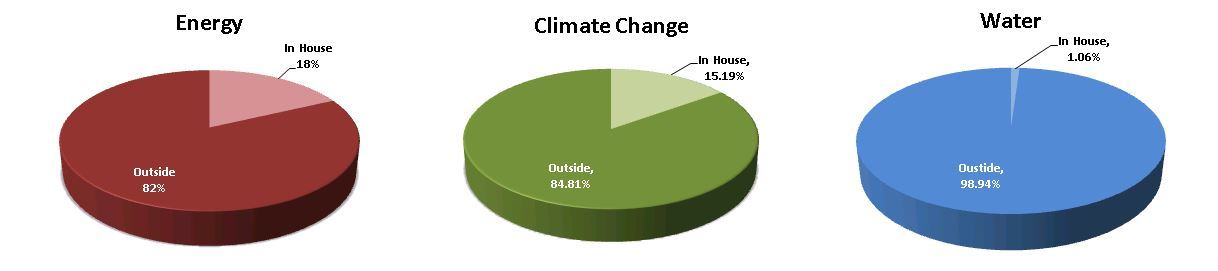

The product our company considered for the LPC was the painted sunshade. The first step in the process of measuring the painted sunshade’s handprint was to determine its footprint using a process called a life cycle assessment (LCA). The LCA focused on three key impact areas: energy, water and climate. All of the inputs in these areas were estimated using global standards for each activity throughout the life of the product: producing aluminum, transporting it to the extruder, extruding it, transporting it to use, finishing it, shipping it out and everything in between. We found that the inputs outside the factory made up the majority of their product’s footprint. To be net positive, they needed to offset the inputs for the entire process, not just at the plant.

Creating handprints offsets the impacts of the total life cycle of the product. We used information from a study performed by John Carmody at the University of Minnesota as the basis for determining the energy, water and climate effects of our products during the use phase (when are products are on a building). They applied data from six cities, multiple sunshade configurations and glazing types for 648 total input reduction scenarios. The point at which the sunshades provide a payback for energy, climate and water usage vary by sunshade size, glazing type climate area. In every case, however, forecasted savings are greater than the inputs required to make them. In climates where cooling loads are high, the payback time is shorter.

Lisa Britton, CSI, CCPR, LEED AP BD+C, GGP, is director of sales and marketing/sustainability champion, and Laura Turner is sustainability intern at Industrial Louvers Inc., Delano, Minn. To learn more, visit www.industriallouvers.com or call (763) 972-7011.