In the September issue, the staff of Metal Construction News devotes itself to what we think is the most important topic in the construction industry. We address it from multiple angles, identifying new trends, new technologies and new management systems. Sit through any association meeting in the construction industry, and you will hear the room grow quiet and serious the moment safety issues are raised.

Construction can be dangerous, but changes over the last few years are making it safer than ever

The mantra, “Every worker goes home at the end of the day” has real meaning when you’ve been on a job site where a fatality or serious injury has occurred.

“58 percent of Americans working in construction—the industry that sees the most workplace fatalities each year—feel that safety takes a back seat to productivity and completing job tasks. What’s more, 51 percent say management does only the minimum required by law to keep employees safe, and 47 percent say employees are afraid to report safety issues.”

National Safety Council, Employee Perception Surveys, 2017

Unfortunately, that occurrence is not that uncommon in construction. The national media gives considerable attention to the dangers police officers face on the job, and rightfully so. The courage they exhibit to protect us from people who would harm us is beyond admiration. But at the end of the day, a police officer is more likely to go home to his family than an iron worker, roofer, laborer or even construction supervisor. (See box on page 16.)

What used to pass for safety 10 or 15 years ago would be laughed at today. New and better regulations, improved safety management, better equipment and increased awareness of safe construction practices have all contributed to improved safety performance. Worker safety is even being taken into consideration as early as the conceptual design phase.

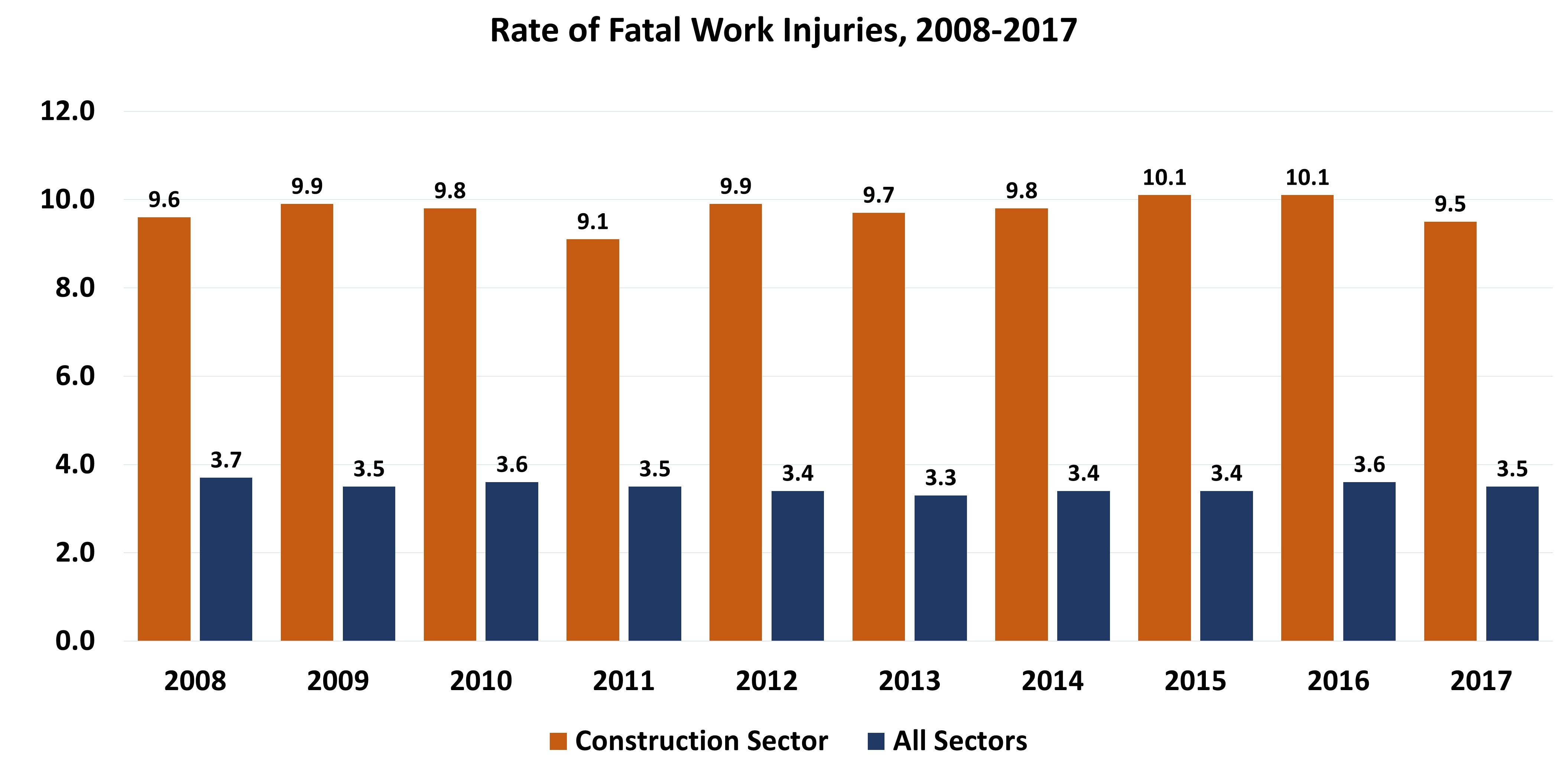

The rate of fatalities in the construction sector is about 2.5 times greater than the rate across all industries.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

An Ironclad Approach to Safety

In an era dominated by an aging construction workforce, the Ironworkers International has initiated two programs that provide new career avenues for aging workers and focus on improving safety performance. The union’s general president, Eric Dean, who is co-chair of IMPACT(the labor-management partnership) along with William W. Brown, chair, Ben Hur Construction Co., St. Louis, have led the safety department to develop the “Ironworker Safety Directory Training Course” and the “Ironworker Safety Supervisor Certification” program. Both initiatives fill needs for workers.

Safety Director Training Course

The safety director course is designed to raise the standard of safety performance and provide employment opportunities for ironworkers to become full-time safety directors. Steve Rank is the executive director of Safety and Health for the Ironworkers. “I’ve had calls for years from people wanting to know if I had any ironworker safety directors that can take over their safety department,” he says, “because the kind of safety personnel they get off the street have never eaten out of a lunchbox or been an ironworker. That has resulted in the same problems with not understanding the work we do, the hazards or the regulations that pertain to them.

“On the other hand, I have ironworkers that have called me wanting to know how they can get into the safety end of it because they have a bad back, neck, shoulder or knee, but they have to work for another 15 years.” The Ironworkers decided to take these members from the field and give them a new skill set, solving two problems in one initiative.

The safety director course was started two years ago, and 504 workers have been trained. The course is a 40-hour curriculum in 10, 4-hour classes. Subjects deal with everything from fall protection systems to regulatory compliance and project contracts to evaluating workplace health exposures to steel erection safety activities. It focuses on both the practical, day-to-day safety practices and learning the management skills necessary to develop and execute a safety program.

Men and women who enter the trades often do so because they enjoy the hands-on feeling of accomplishment and they don’t like doing paperwork. “I can take the best ironworker in Chicago,” says Rank, “and put him to work for an erector company with 180 employees in three states. It’s Monday morning, and he’s got the whole safety program. He’s the full-time safety director. I guarantee that by 10 o’clock in the morning he’d be quitting.” That ironworker knows how to build the building, but he doesn’t know how to manage the safety program.

“That’s what these 10 classes do,” says Rank. “They prime the pump. We provide them with templates on how to develop a job hazard analysis for setting rigid frames, for example. Aerial lift training. Guying and bracing. Landing roof bundles on secondary structural members. We make sure they understand this from a safety perspective.”

Safety Supervisor Certification Program

It’s not unusual for people who excel in one job to get promoted to a job that doesn’t fit their skill set and places them in an awkward position. In construction, capable, efficient tradespeople get promoted to supervisory positions that take them away from the hands-on work they excel at and give them duties that are vastly different. Some flourish. Some flounder. But one aspect of this on the safety side is especially troubling.

“We have ironworkers who don’t want to be safety directors,” says Rank. “They wouldn’t do it for a million dollars. But if they are considered a supervisor they are considered to be a company management representative.”

If a foreman is violating an OSHA standard while erecting a metal building that is witnessed by OSHA, it is no different than if the owner of the company was there. That takes away the employer’s right of unpreventable employee misconduct defense.

Because of that, many jobs and companies require supervisor certifications. There are a lot of organizations that train and provide those certifications, but the Ironworkers wanted to develop their own that would be specific to their trade and fulfill owners’ requirements for safety trained supervisors. “We’ll be the first trade union to develop a specific safety certification for our members,” says Rank. “We want to provide project owners, general contractors and our contractors with the best ironworker safety supervisors to help prevent workplace incidents and achieve outstanding safety performance.”

The certification will be accredited by the International Accreditation Service (IAS), which also accredits the Metal Building Manufacturers Association’s AC472 program and the Metal Building Contractors & Erectors Association’s “Metal Building Inspection Assembler” accreditation (AC478).

Rank anticipates rolling out the pilot program in California in January 2020 and hopes to introduce the complete program to the annual instructor training event in July in Ann Arbor, Mich. The certification training will be available through the 157 training facilities across North America.

“We’re inviting owners and general contractors to evaluate the program, as well as topnotch safety people from General Motors, Turner Construction, Google and others,” says Rank. “We want them to be hard on us because we want to make this industry’s first, the best. At the end of the day, we want people to feel confident that we’re making every effort to address hazards and supervisors for metal building erection. To prevent structural collapse. Falls. Hoisting and rigging incidents. Anything that can happen during the erection of metal buildings.”

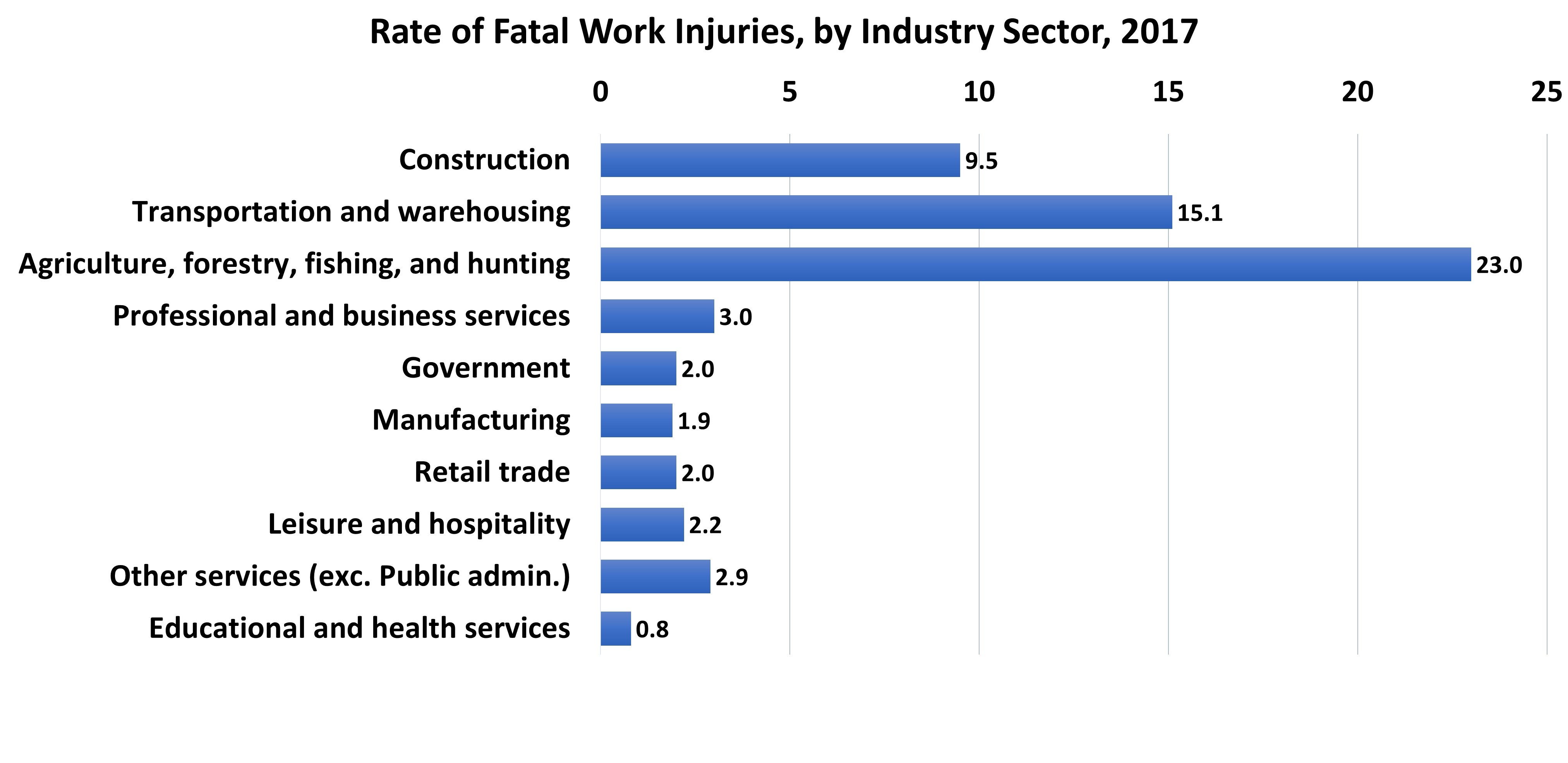

Construction ranks third in the most dangerous sector of the U.S. economy. Transportation fatal injuries numbers are driven by the high incident of traffic fatalities. The Agricultural, forestry, fishing and hunter sector tops the chart because of the incredibly dangerous jobs in commercial fishing and logging.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

General Trends

Craig Shaffer, CSP, has been a safety consultant for nearly 30 years and is president of Safety Works Inc., Dillsburg, Pa. He partners regularly with metal building contractors and erectors to help them improve their safety processes.

The best example he gives of the changes in safety is the reaction to the new respirable crystalline silica regulation that OSHA rolled out. “There was a lot of concern. There were a lot of parts and pieces to that regulation,” he says, “And a lot of people were concerned how OSHA was going to look at it … There were a lot of requirements for written programs, training, testing. Two years later, I can’t speak for everywhere around the country, but it hasn’t been bad around here. Every job is going to have silica. The exposure is there for just about every trade. In our experience, the inspectors are certainly looking at it, but if you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing—if you’re using water or some kind of HEPA filter dust collection—the inspectors have been leaving you alone.” In other words, they are going to go after the people who aren’t doing anything rather than spend their time scrutinizing the contractors trying to do it right.

Overall, Shaffer identifies four areas where he sees major trends in safety:

- Companies are planning safety into the production process

- Use of performance metrics

- Safety as part of the design process

- New technology

We’ll focus here on the first two points. For more information about new technologies, go to the “Safety Technology” feature.

The impetus for much of the focus on safety during the preconstruction phase is twofold. First, this is the best time to integrate safety measures into a project in a manner that will minimize productivity impact. Also, there are often project-specific contractual obligations to meet. Some projects require site-specific safety plans; others require a safety representative to be on-site; and yet others require OSHA training. In fact, requirements for workers to have OSHA 10 training—and even supervisors to have OSHA 30 training within the last five years— “has become a law in a number of big cities, like New York” says Shaffer, “and this is starting to become a common requirement on larger projects and for large-scale general contractors. It’s not an OSHA thing, but it’s becoming the norm.”

Use of Safety Performance Metrics

Shaffer also notes the increasing reliance on performance measurements in managing safety issues. Management consultant and educator Peter Drucker famously said, “What gets measured, gets managed.” You could argue that there are very few areas where that has been taken more to heart than in safety management. In fact, recording and tracking incidents is a major portion of managing safety and meeting OSHA expectations.

But it’s not just OSHA that is driving the metrics trend. “More and more projects, especially the larger ones,” says Shaffer, “are requiring contractors to prequalify for work. They prequalify off a number of things. It might be their experience modification factor, OSHA fine history for the last three or five years, of if they’ve had any bad accidents in that period of time.”

These requirements move into a couple of measurements called “Incident Rate” and “DART Rate.” OSHA requires companies with more than 10 employees to report Incident Rates, types of incidents and DART Rate every year. A recordable incident is any incident that resulted from an exposure or event in the workplace and that required some type of medical treatment or first aid. The incident rate is the number of recordable incidents per 100 employees. The DART rate is a calculation that describes the number of recordable injuries and illnesses per 100 full-time employees that results in days away from work, restricted work activity and/or job transfer.

“For construction,” says Shaffer, “the average Incident Rate is about 2.9.” That means 2.9 recordable incidents per 100 employees in a year. Shaffer worries that the average is a deceiving number that is based heavily on very large companies.

“It really hurts small companies,” he says. “If I’m a company with 25 people and I have one OSHA recordable, my rate is four. That isn’t necessarily true, but that’s how the math works. With one recordable, I’m almost twice the national averages.

“I’m not worried about it from the OSHA standpoint … What I worry about is more people are using that number as a barometer of how good your safety program is. My personal belief is that the number measures luck and honesty. I see plenty of companies that have no recordables and I go out to their job site and it’s a mess. They’ve either been lucky or …” Shaffer is reluctant to say that some companies will game the system by treating work injuries off the books, which is illegal.

“I think it’s the absolute worst measure of safety there is. I hope to see a trend away from using Incident Rate and DART Rate from being used for prequalification,” says Shaffer. “There are measurements out there. Mod factors isn’t a bad one.”