The unique façade of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum (USOPM) in Colorado Springs, Colo., stood out among all of the projects entered into the 2020 Metal Construction News Building and Roofing Awards. Calling it incredible and elegantly done, the judges declared it this year’s Overall Winner. “Overall, just a fantastic execution of a great piece of architecture, but most importantly, the use of metal as a very predominant building material,” says George Garcia, AIA, NCARB, RIBA, founder/principal architect at garcia architecture + design, San Luis Obispo, Calif.

New museum is inspired by energy and grace of Olympic and Paralympic athletes

Photo: Brennan Photo Video

Located at the base of the Rocky Mountains, the USOPM is a tribute to the Olympic and Paralympic movements with Team USA athletes up front and center. The museum anchors the new City for Champions District, forming a new axis that bridges downtown Colorado Springs to the America the Beautiful Park to the west. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro Architects (DSRNY), New York City, the 60,0000-square-foot, four-story building features 20,000 square feet of galleries, a state-of-the-art theater, event space and cafe. Targeting LEED Gold certification, the museum opened to the public on July 30, 2020.

From the outdoor public realm to all of the galleries within, Ben Gilmartin, partner, DSRNY, says the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum wanted to build one of the most inclusive and accessible museums in America. “Our design extends the openness of the public realm into the heart of the museum, through its perimeter walls, to bring its cultural offerings out to the city,” he says.

Inside, the goal was to create a connected and seamless experience for people of all abilities. “From the earliest stages of design, the team consulted a committee of Paralympic athletes and persons with disabilities to ensure that, from entrance to exit, all visitors with or without disabilities could tour the USOPM facility together and share a common path,” Gilmartin explains. “The museum also incorporates a state-of-the-art check in system where visitors can register any personal needs on an electronic tag, such as being hard of hearing or difficulty reading small print. The exhibits are pre-programmed to automatically adjust to meet those requirements.”

Photo: Brennan Photo Video

Pinwheel Form

The museum is designed in four petal-like volumes that spiral out from a central atrium. Guests arrive and are transported to the top of the museum via elevator, where they wind their way around the spiraling exhibit walls, tracing the legacy of Team USA.

According to Gilmartin, every aspect of the design strategy was motivated by the goal of expressing the extraordinary athleticism and progressive values of Team USA. “A taut aluminum façade flexes and twists over the building’s dynamic pinwheel form, drawing inspiration from the energy and grace of Olympians and Paralympians. Inside, descending galleries are organized along a continuous spiral, enabling visitors of all abilities to have a shared, common experience along a universal pathway.”

Holly Deichmann Chacon, associate principal, DSRNY, notes that the building’s primary structural system is a steel frame superstructure, drilled shaft caisson foundations and cast-in-place concrete lateral cores. “The highly irregular, sloping and nonorthogonal steel superstructure includes custom solutions of steel-to-steel and steel-to-concrete connections, a 60-ton steel truss supported by tilted columns and struts, discontinuous lateral floor and roof diaphragms, a suspended steel-framed atrium roof surrounded by clerestory glazing, and architecturally exposed structural concrete floor slabs,” she explains. “The ruled surfaces of the USOPM’s sculptural skin have no orthogonal relationship to the superstructure as the skin morphs across multiple sloping floor levels. The vertical and horizontal transitions between ruled surfaces and the superstructure were coordinated with architectural detailing to determine appropriate girt/support locations and required movement joints due to thermal, lateral, and occupancy movements. As a result, the system appears joint free.”

Photo: Brennan Photo Video

Aluminum Petal Façade

To design the museum’s façade, which is made up of more than 9,000 folded, diamond-shaped anodized aluminum panels, each unique in size and shape, DSRNY worked closely with fabricator and installer MG McGrath, Maplewood, Minn. The museum’s façade expresses the twisting and turning of the otherwise black-box museum. “It’s a dynamic surface and we wanted the skin to feel tightly stretched onto a uniform surface of the museum structure inside,” says Yushiro Okamoto, associate, DSRNY. “We wanted visitors to feel the tension in the surface, like a taut suit.”

Okamoto notes that while they initially looked at using stainless steel, aluminum was better suited for the form of the building and the geometry of each panel required folding by hand after laser cutting. Aluminum was also more economical from a weight standpoint. “The aluminum petals articulate ruled surfaces, spiraling and twisting up from the ground and aspirationally gesturing toward taking flight,” Okamoto explains. “The outer skin wraps over the galleries and folds itself to form the walls in the atrium, just like origami. Where surfaces overlap, daylight enters the building and that orients the visitor and marks their trajectory through the museum.”

The designers spent a long time determining the right finish for the aluminum because while they did not want it to be too shiny or reflective, they wanted it play with light and shadow. “Each panel and every gentle fold is animated by the extraordinary light quality in Colorado Springs,” he continues. “The light moves across the surface, producing gradients of color and light, from mid-day brighter light as the clouds change to the beautiful colors of sunset. It gives the building another sense of motion and dynamism that embodies the spirit of the museum. There’s a scaliness and shadows that define the geometry and movement of the surface.”

“The level of craftsmanship involved with this, and how shade and shadow become a part of this is incredible,” notes Steven Ginn, founding principal at Steven Ginn Architects, Omaha, Neb.

Photo: Brennan Photo Video

Twisting Geometry

To conform to the twisting geometry of the museum, Okamoto says the design team collaborated with Minneapolis-based Radius Track Corp. to develop a curved sheathing, with cold-formed metal framing, which is attached to the primary steel structure with an axial connection. Each panel is fastened to the metal framing with 2 3/8-inch Z-girts that run through to the sheathing. “It was an exciting and collaborative learning process for all of us,” he says.

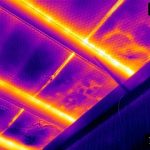

MG McGrath fabricated approximately 100,000 square feet of Muskegon, Mich.-based Lorin Industries Inc.’s 0.063-inch Class 1 anodized aluminum ClearMatt Brushed, in 48-inch by 137-inch sheets, into a custom rainscreen panel system. To accommodate the building’s complex geometry, each diamond-shaped panel is unique and shaped slightly different. Each panel is lifted 1-inch at one corner to create a scale-like directionality that tracks sunlight. The custom panels are installed on the exterior façade, low-sloping walls and roof, as well as the interior vestibule ceiling.

According to Ilja Adjoskin, senior project manager at MG McGrath, each panel had to be unique because of the curved and sloping geometry. “The challenge of making all of the requirements fit together in a way that looked good, and performed the way it should was very difficult and our team designed and tested many variations of panels to find something that fit the architects’ vision with the performance requirements,” he explains. “It is difficult to make a 3-D panel system that fits together and is watertight. It is difficult to make a panel system that curves and still interlocks with adjacent panels with different curves. And it is difficult to make a panel system that slopes up and over sides of a building. All of these things are difficult on their own and we had to design and execute a panel system that can do it all while still looking good, protecting the building from water intrusion, and not going over budget.”

Photo: Brennan Photo Video

To complete the project, a high level of coordination was required between all of the teams and partners involved. “Precision was the name of the game on this project and there wasn’t any room for mistakes or even the slightest variation,” Adjoskin says. “Material placements and quantities were individually mapped out literally down to the nuts and bolts. If one thing was even slightly out of place, it threw everything else off for everyone. Open communication, a master project model, and matching field scans to the model in a way that was visible to everyone was incredibly challenging. Every team member on this project had to be a team player with great communication, a perfection mindset, and a solutions-oriented way of thinking.”

“It’s taking manufacturing to a new level in terms of each of these pieces being a unique piece, probably not replicated anywhere on the building,” says Tim Wybenga, LEED AP, principal at TVA Architects, Portland, Ore., “and the ability of the fabricator to do that and execute it to this level is outstanding. It’s really phenomenal.”

Additionally, MG McGrath installed more than 11,000 square feet of Resliance Cassette curtainwall framing from Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope, Dallas, with VE1-85 insulated glass and spandrel from Viracon Inc., Owatonna, Minn. MG McGrath also fabricated and installed more than 4,824 square feet of MG McGrath’s D-set panel system with 4-mm Vitrabond aluminum composite material from Fairview Architectural North America, Bloomfield, Conn., for various pieces of trim. The project also features 350 square feet of glass guard rails and glass handrails, folding glass wall partitions from Nana Wall Systems Inc., Corte Madera, Calif., and glass doors with accompanying hardware from Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope.