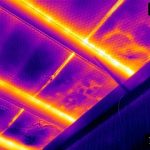

We all know how condensation starts in a metal building—warmer moist air comes in contact with cold surfaces (such as rafters, purlins, roof and wall sheeting, windows and other fenestrations) and cooler areas within the building envelope, such as the insulation system.

Common condensation problems and how to prevent them

When that warm air comes in contact with cold air, it loses its ability to retain vapor, thus resulting in the release of excessive moisture in the air; in other words: condensation. When condensation occurs within the building envelope, it can severely compromise the insulating value of the fiberglass.

That’s review for the majority of us. But what may not be review is how to correctly and efficiently prevent that warm air from infiltrating the building envelope. Placing an emphasis on condensation prevention could save thousands of dollars, plus plenty of extra time and frustration.

Stopping Moisture Migration in the Envelope

Metal buildings are unique in the way they’re insulated. A typical metal building insulation application includes an exposed vapor retarder laminated to blanket fiberglass insulation, or a separate material covering the purlins and the girts (e.g., liner system).

The vapor retarder is exposed to the interior of the building because that is usually the warm side of the structure (an exception to this is when the interior of the building is a cooler or freezer, and the inside temperature is lower than the outside temperature). Remember that moisture travels from areas of higher vapor pressures to lower vapor pressures, so a vapor retarder should be placed at the point of the highest vapor pressure, i.e., the interior of the warmer side of the structure.

Because the vapor retarder—often interchangeably referred to as a vapor barrier—is exposed, it is essentially the last line of defense against excessive moisture migration into the fiberglass cavity. Contrary to what many people think, a vapor retarder is not designed to completely stop the flow of moisture. We actually want a small amount of vapor to pass through the envelope because it allows the envelope to breathe. Instead, a vapor retarder is designed to retard, or reduce, the movement of moisture.

The amount of moisture that passes through a vapor retarder is dictated by the permeance of the vapor retarder, which is known as a perm rating. Perm ratings are calculated based off of the ASTM E96 test for determining vapor transmission ofmaterials. A perm rating ranges from .10 to 10; the lower the perm rating, the less vapor transmission and the more effective the vapor retarder will be. There are two widely accepted vapor retarder classification systems, one from The International Code Council (ICC) and the other from The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).

Perm Ratings

Perm ratings for metal building applications range from 0.09 and 0.02, with the Class 1 or Vapor Impermeable being the most commonly used in metal buildings. Vapor retarders with a perm rating of 1.0 or above are considered to be at a minimum performance level. Vapor retarders with a perm rating of 0.5 and higher may not be suitable for high humidity and higher. Remember, though, that nothing can stop water vapor transmission 100 percent of the time.

The type of vapor retarders that we use in the metal building industry are known as flexible membranes, which consist of foils, coated papers or plastic films. The most commonly used vapor retarders in our industry are made from a polypropylene white or black film, and often contain a fiberglass or polyester scrim.

So, how does the perm rating really impact a project? Remember that vapor retarders do not completely prevent moisture migration, they only slow the process. Though minimal, the water vapor transmission can accumulate over time and turn into liquid moisture dripping down from the affected area. Translation: major condensation issues. The better the perm rating and thus less permeable the vapor retarder, the less likely moisture will pass through.

In addition to the accumulation of water vapor through a highly permeable vapor retarder, there’s another more harmful culprit of condensation in the building envelope: punctures and holes in the vapor retarder. Warm air naturally gravitates towards cold air, and a hole in the vapor barrier is the path of least resistance. The moisture transmission method can introduce a large amount of moisture into the cross-section of the thermal envelope, leading to potentially devastating consequences, such as decreased thermal performance and moisture dripping onto equipment and products.

Bill Beals is the district manager at Therm-All Inc., North Olmsted, Ohio. To learn more, visit www.therm-all.com.